Apr 2 2015

Therapeutic agents intended to reduce dental plaque and prevent tooth decay are often removed by saliva and the act of swallowing before they can take effect. But a team of researchers has developed a way to keep the drugs from being washed away.

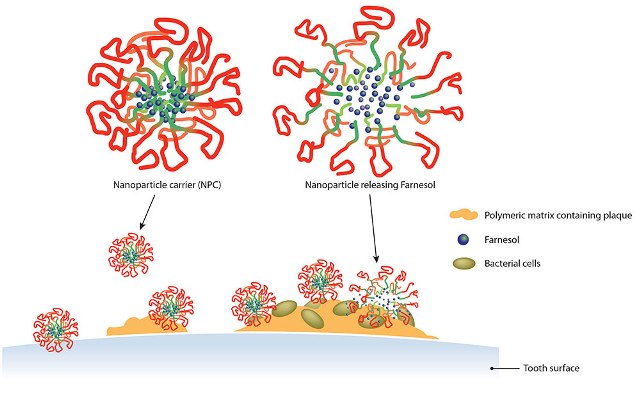

Farnesol is released from the nanoparticle carriers into the cavity-causing dental plaque. (Graphic by Michael Osadciw/University of Rochester)

Farnesol is released from the nanoparticle carriers into the cavity-causing dental plaque. (Graphic by Michael Osadciw/University of Rochester)

Dental plaque is made up of bacteria enmeshed in a sticky matrix of polymers—a polymeric matrix—that is firmly attached to teeth. The researchers, led by Danielle Benoit at the University of Rochester and Hyun Koo at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Dental Medicine, found a new way to deliver an antibacterial agent within the plaque, despite the presence of saliva.

Their findings have been published in the journal ACS Nano.

“We had two specific challenges,” said Benoit, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering. “We had to figure out how to deliver the anti-bacterial agent to the teeth and keep it there, and also how to release the agent into the targeted sites.”

To deliver the agent—known as farnesol—to the targeted sites, the researchers created a spherical mass of particles, referred to as a nanoparticle carrier. They constructed the outer layer out of cationic—or positively charged—segments of the polymers. For inside the carrier, they secured the drug with hydrophobic and pH-responsive polymers.

The positively-charged outer layer of the carrier is able to stay in place at the surface of the teeth because the enamel is made up, in part, of HA (hydroxyapatite), which is negatively charged. Just as oppositely charged magnets are attracted to each other, the same is true of the nanoparticles and HA. Because teeth are coated with saliva, the researchers weren’t certain the nanoparticles would adhere. But not only did the particles stay in place, they were also able to bind with the polymeric matrix and stick to dental plaque.

Since the nanoparticles could bind both to saliva-coated teeth and within plaque, Benoit and colleagues used them to carry an anti-bacterial agent to the targeted sites. The researchers then needed to figure out how to effectively release the agent into the plaque.

A key trait of the inner carrier material is that it destabilizes at acidic—or low pH—levels, such as 4.5, allowing the drug to escape more rapidly. And that’s exactly what happens to the pH level in plaque when it’s exposed to glucose, sucrose, starch, and other food products that cause tooth decay. In other words, the nanoparticles release the drug when exposed to cavity-causing eating habits—precisely when it is most needed to quickly stop acid-producing bacteria.

The researchers tested the product in rats that were infected with Streptococcus mutans—a microbe that causes tooth decay. “We applied the test solutions to rats’ mouths twice daily for 30 seconds, simulating what a person might do using a mouth rinse morning and night,” said Hyun Koo, a professor in the Department of Orthodontics and co-senior author of the work. “When the drug was administered without the nanoparticle carriers, there was no effect on the number of cavities and only a very small reduction in their severity. But when it was delivered by the nanoparticle carriers, both the number and severity of the cavities were reduced.”

Plaque formation and tooth decay are chronic conditions that need to be monitored through regular visits to the dental office. The researchers hope their results will someday lead to better—and perhaps permanent—treatments for dental plaque and tooth decay, as well as other biofilm-related diseases.