Jan 9 2020

Directional antennas are devices that transform electrical signals into radio waves, radiating them in a specific direction. This principle, which enables reduced interference and improved performance, has proved advantageous in radio wave technology and could also be applicable to miniaturized light sources.

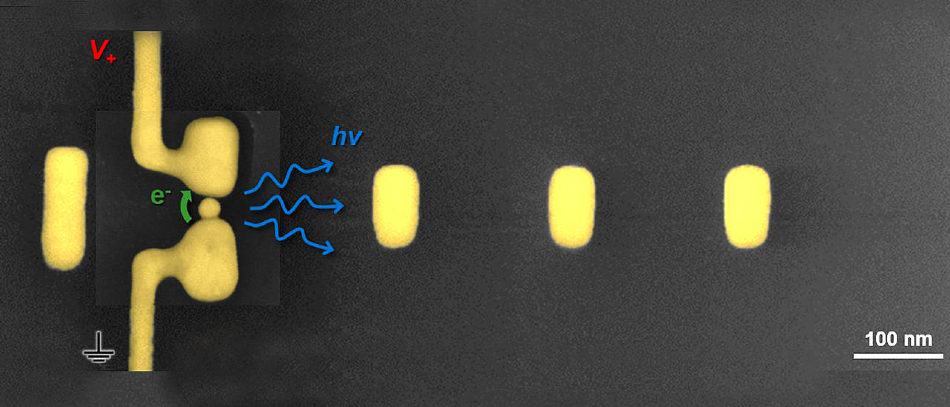

Let there be light—and it was directional: The world’s first electrically powered Yagi-Uda antenna was built at the University of Würzburg’s Department of Physics. Image Credit: Department of Physics; Physikalisches Institut.

Let there be light—and it was directional: The world’s first electrically powered Yagi-Uda antenna was built at the University of Würzburg’s Department of Physics. Image Credit: Department of Physics; Physikalisches Institut.

In any case, nearly all Internet-based communication makes use of optical light communication. It is possible to use directional antennas for light transfer data between various processor cores at the speed of light, with little loss. Such directional antennas can be made to work with visible light’s very short wavelengths by shrinking their size to the nanometer scale.

In a leading publication, physicists from the University of Würzburg have now laid the foundation for this technology. For the first time, they have explained ways to synthesize directed infrared light by making use of an electrically driven Yagi-Uda antenna made of gold, in the Nature Communications magazine.

The antenna was designed by the nano-optics working group led by Professor Bert Hecht, who holds the Chair of Experimental Physics 5 at the University of Würzburg. The antenna has been named “Yagi-Uda” after Hidetsugu Yagi and Shintaro Uda, the two Japanese scientists who invented the antenna in the 1920s.

Applying the Laws of Optical Antenna Technology

What would be the appearance of a Yagi-Uda antenna for light? “Basically, it works in the same way as its big brothers for radio waves,” noted Dr René Kullock, one of the members of the nano-optics group. When an AC voltage is applied, electrons in the metal start to vibrate, and consequently, the antennas emit electromagnetic waves.

In the case of a Yagi-Uda antenna, however, this does not occur evenly in all directions but through the selective superposition of the radiated waves using special elements, the so-called reflectors and directors. This results in constructive interference in one direction and destructive interference in all other directions.

Dr René Kullock, Nano-Optics Group, University of Würzburg

Thus, an antenna such as this can only receive light coming from the same direction, upon being operated as a receiver.

It is technically difficult to apply the laws of antenna technology to nanoscale antennas emitting light. In the past, the Würzburg physicists demonstrated that the principle of an electrically driven light antenna can work. However, to develop a comparatively complex Yagi-Uda antenna, they needed to develop new concepts.

Eventually, they were successful in developing an advanced production method.

We bombarded gold with gallium ions which enabled us to cut out the antenna shape with all reflectors and directors as well as the necessary connecting wires from high-purity gold crystals with great precision.

Bert Hecht, Professor and Chair of Experimental Physics 5, University of Würzburg

Subsequently, a gold nanoparticle was placed by the physicists as the active element so that it is in contact with one wire of the element while being at a distance of just 1 nm from the other wire.

“This gap is so narrow that electrons can cross it when voltage is applied using a process known as quantum tunnelling,” noted Kullock. This charge motion produces vibrations with optical frequencies in the antenna. These vibrations are emitted in a particular direction due to the unique arrangement of the reflectors and directors.

Accuracy Dependent on Number of Directors

The Würzburg physicists were surprised by the unique property of their innovative antenna that emits light in a specific direction, irrespective of its small size. Similar to the radio wave antennas, the “larger counterparts” of the new optical antenna, the directional light emission accuracy of the new antenna is governed by the number of antenna elements.

This has allowed us to build the world’s smallest electrically powered light source to date which is capable of emitting light in a specific direction.

Bert Hecht, Professor and Chair of Experimental Physics 5, University of Würzburg

However, more research efforts are required before the new device can be readily used in practice. The researchers firstly must work on the counterpart that receives light signals. Next, the stability and efficiency of the device must be elevated.