Jan 9 2015

Even when building big, every atom matters, according to new research on particle-based materials at Rice University.

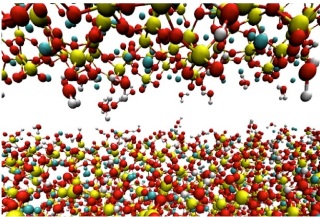

A calcium-silicate-hydrate (aka cement) tip hovers above a smooth tobermorite surface in a computer simulation by Rice University scientists. The researchers studied how atomic-level forces in particulate systems interact when friction is applied. Their calculations show such materials can be improved for specific applications by controlling the materials’ chemical binding properties. (Credit: Shahsavari Group/Rice University)

A calcium-silicate-hydrate (aka cement) tip hovers above a smooth tobermorite surface in a computer simulation by Rice University scientists. The researchers studied how atomic-level forces in particulate systems interact when friction is applied. Their calculations show such materials can be improved for specific applications by controlling the materials’ chemical binding properties. (Credit: Shahsavari Group/Rice University)

Rice researchers Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Saroosh Jalilvand have published a study showing what happens at the nanoscale when “structurally complex” materials like concrete — a random jumble of elements rather than an ordered crystal — rub against each other. The scratches they leave behind can say a lot about their characteristics.

The researchers are the first to run sophisticated calculations that show how atomic-level forces affect the mechanical properties of a complex particle-based material. Their techniques suggest new ways to fine-tune the chemistry of such materials to make them less prone to cracking and more suitable for specific applications.

The research appears in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

The study used calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H), aka cement, as a model particulate system. Shahsavari became quite familiar with C-S-H while participating in construction of the first atomic-scale models of the material.

C-S-H is the glue that binds the small rocks, gravel and sand in concrete. Though it looks like a paste before hardening, it consists of discrete nanoscale particles. The van der Waals and Coulombic forces that influence the interactions between the C-S-H and the larger particles are the key to the material’s overall strength and fracture properties, said Shahsavari. He decided to take a close look at those and other nanoscale mechanisms.

“Classical studies of friction on materials have been around for centuries,” he said. “It is known that if you make a surface rough, friction is going to increase. That’s a common technique in industry to prevent sliding: Rough surfaces block each other.

“What we discovered is that, besides those common mechanical roughening techniques, modulation of surface chemistry, which is less intuitive, can significantly affect the friction and thus the mechanical properties of the particulate system.”

Shahsavari said it’s a misconception that the bulk amount of a single element — for example, calcium in C-S-H — directly controls the mechanical properties of a particulate system. “We found that what controls properties inside particles could be completely different from what controls their surface interactions,” he said. While more calcium content at the surface would improve friction and thus the strength of the assembly, lower calcium content would benefit the strength of individual particles.

“This may seem contradictory, but it suggests that to achieve optimum mechanical properties for a particle system, new synthetic and processing conditions must be devised to place the elements in the right places,” he said.

The researchers also found the contribution of natural van der Waals attraction between molecules to be far more significant than Coulombic (electrostatic) forces in C-S-H. That, too, was primarily due to calcium, Shahsavari said.

To test their theories, Shahsavari and Jalilvand built computer models of rough C-S-H and smooth tobermorite. They dragged a virtual tip of the former across the top of the latter, scratching the surface to see how hard they would have to push its atoms to displace them. Their scratch simulations allowed them to decode the key forces and mechanics involved as well as to predict the inherent fracture toughness of tobermorite, numbers borne out by others’ experiments.

Shahsavari said atomic-level analysis could help improve a broad range of non-crystalline materials, including ceramics, sands, powders, grains and colloids.

Jalilvand is a former graduate student in Shahsavari’s group at Rice and is now a Ph.D. student at University College Dublin. Shahsavari is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering and a member of the Richard E. Smalley Institute for Nanoscale Science and Technology at Rice.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) supported the research. Supercomputer resources were provided by the National Institutes of Health and an IBM Shared University Research Award in partnership with CISCO, Qlogic and Adaptive Computing, and the NSF-funded Data Analysis and Visualization Cyber Infrastructure administered by Rice’s Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.

Source: http://www.rice.edu/