Sep 24 2007

An international team including scientists from the London Centre for Nanotechnology (LCN) today publishes findings in the journal ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’ (PNAS) demonstrating the dramatic effects of quantum mechanics in a simple magnet. The importance of the work lies in establishing how a conventional tool of material science – neutron beams produced at particle accelerators and nuclear reactors – can be used to produce images of the ghostly entangled states of the quantum world.

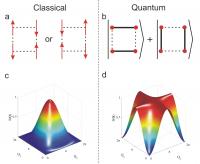

For simplicity, the team focused on a square of spins, the tiny bar magnets associated with the electrons in the copper atoms in the organometallic material studied by the researchers. The left (c) shows a calculated neutron image for these spins when they behave as classical objects (a), while the right (d) shows the image when they are entangled (b). The images are dramatically different in the two cases, taking the form of a nearly circular spot for the classical case and a cross for the quantum, entangled state.

For simplicity, the team focused on a square of spins, the tiny bar magnets associated with the electrons in the copper atoms in the organometallic material studied by the researchers. The left (c) shows a calculated neutron image for these spins when they behave as classical objects (a), while the right (d) shows the image when they are entangled (b). The images are dramatically different in the two cases, taking the form of a nearly circular spot for the classical case and a cross for the quantum, entangled state.

At the nano scale, magnetism arises from atoms behaving like little magnets called ‘spins’. In ferromagnets - the kind that stick to fridge doors - all of these atomic magnets point in the same direction. In antiferromagnets, the spins were thought to spontaneously align themselves opposite to the adjacent spins, leaving the material magnetically neutral overall. The new research shows that this picture is not correct because it ignores the uncertainties of quantum mechanics. In particular, at odds with everyday intuition, the quantum-mechanical physical laws which operate on the nano-scale allow a spin to simultaneously point both up and down. At the same time, two spins can be linked such that even though it is impossible to know the direction of either by itself, they will always point in opposite directions – in which case they are ‘entangled’.

With their discovery, the researchers demonstrate that neutrons can detect entanglement, the key resource for quantum computing.

One of the lead authors of the work, Professor Des McMorrow from the LCN, comments: “When we embarked on this work, I think it is fair to say that none of us were expecting to see such gigantic effects produced by quantum entanglement in the material we were studying. We were following a hunch that this material might yield something important and we had the good sense to pursue it.”

The researchers’ next steps will be to pursue the implications for high temperature superconductors, materials carrying electrical currents with no heating and which bear remarkable similarities to the insulating antiferromagnets they have studied, and the design of quantum computers.