Oct 2 2008

Flexible filamentous viruses make up a large fraction of known plant viruses and are responsible for more than half the viral damage to crop plants throughout the world. New details of their structures, which were poorly understood, have been revealed by scientists using a variety of sophisticated imaging techniques at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and collaborating institutions.

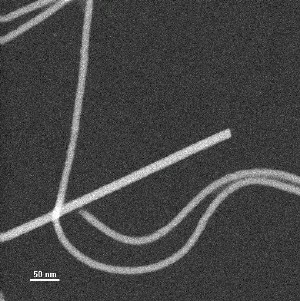

Typical STEM image of unstained specimen used for mass-per-unit-length measurement. Straight, thicker particle is tobacco mosaic virus internal control. Curved particles are soybean mosaic virus.

Typical STEM image of unstained specimen used for mass-per-unit-length measurement. Straight, thicker particle is tobacco mosaic virus internal control. Curved particles are soybean mosaic virus.

These findings, just published in the October 1, 2008, issue of the Journal of Virology, may lead to new ways to protect crop plants from viruses and other forms of damage. The structural information may also benefit scientists interested in using viruses as agents of biotechnology to coax plants to produce other useful products, such as pharmaceuticals.

“These are very important viruses, and we knew almost nothing about their detailed structure before these studies,” said Gerald Stubbs, a structural biologist at Vanderbilt University and lead author on the paper. “If you are to come up with any molecular way of combating these plant diseases, you need to know the details of their structures.” For example, structural information could help scientists design molecules that interfere with the virus’s ability to infect plant cells.

The scientists from Vanderbilt, Brookhaven, Boston University, Illinois Institute of Technology, and the University of Kentucky studied the structures of two plant viruses from unrelated families, the Potyviridae and Flexiviridae, using a combination of complementary imaging techniques — x-ray diffraction at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, cryo-electron microscopy at Vanderbilt, and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) at Brookhaven.

“Brookhaven Lab is home to one of only a few STEM machines in the world,” said co-author Joseph Wall, a biophysicist at Brookhaven who designed and runs the facility.

“These techniques are very complementary,” said Stubbs. “People have been trying to get this structural work started for decades, more than 40 years. It’s been very difficult and there have been a number of obstacles, including the fact that it’s very hard to make good samples of these viruses. But even after we were able to do that, and analyze the structures using x-ray diffraction and traditional electron microscopy, there were a lot of ambiguities in the results. Those techniques gave us several answers and we didn’t know which was correct.”

The STEM technique used at Brookhaven Lab provided the definitive answer. Though by itself, STEM cannot determine the structure of the viral protein coat, it is able to put boundaries on the number of molecules in each “turn” of the spiral-shaped structure. That is, it doesn’t tell you the shape of the molecules but it can count them.

“STEM measures the number of electrons scattered from a length of filament, thereby ‘weighing’ the segment relative to a standard — in this case, tobacco mosaic virus,” said Brookhaven’s Joe Wall. “Knowing the mass per unit length, the subunit size, and the axial repeat gives the number of subunits per turn.” According to Stubbs, “The number of molecules per turn in the helix is the key. It allowed us to determine which structure of the alternatives we’d come up with from other techniques was correct.”

One surprise was that the two viruses the scientists studied, though from unrelated families, turned out to have very similar structures: thin filaments with a spiral structure featuring just under nine molecular subunits per helical turn. “The spiral is so tightly packed that it could not be seen by conventional electron microscopy,” Stubbs said.

Some scientists had predicted there would be similarities between these virus families, but there was a lot of disagreement. This study provides the first experimental evidence that they are indeed similar in shape. That could speed up the pace of discovery because what scientists learn about one family can be applied to the other.

Some potential applications include engineering molecules, based on the viral structure, that interfere with the viruses’ ability to infect plants. Another would be using modified versions of these viruses to introduce into plants genes that help protect the plants from viruses, or even from other forms of damage, such as insect attacks. Still another application would be to use modified viruses to introduce genes instructing plants to make other useful products — for example, antibiotics or other drugs.

This research was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, with funding for several of the research facilities provided by the offices of Basic Energy Sciences (BES) and Biological and Environmental Research (BER) within DOE’s Office of Science, and by the National Institutes of Health.