By using tightly focused light to trigger reactions only where it is needed, multiphoton lithography makes it possible to build complex three-dimensional structures across scales that are difficult to reach with conventional fabrication methods. What began as a laboratory curiosity has become a powerful tool in research working at the boundaries of microfabrication, optics, and bioengineering.1

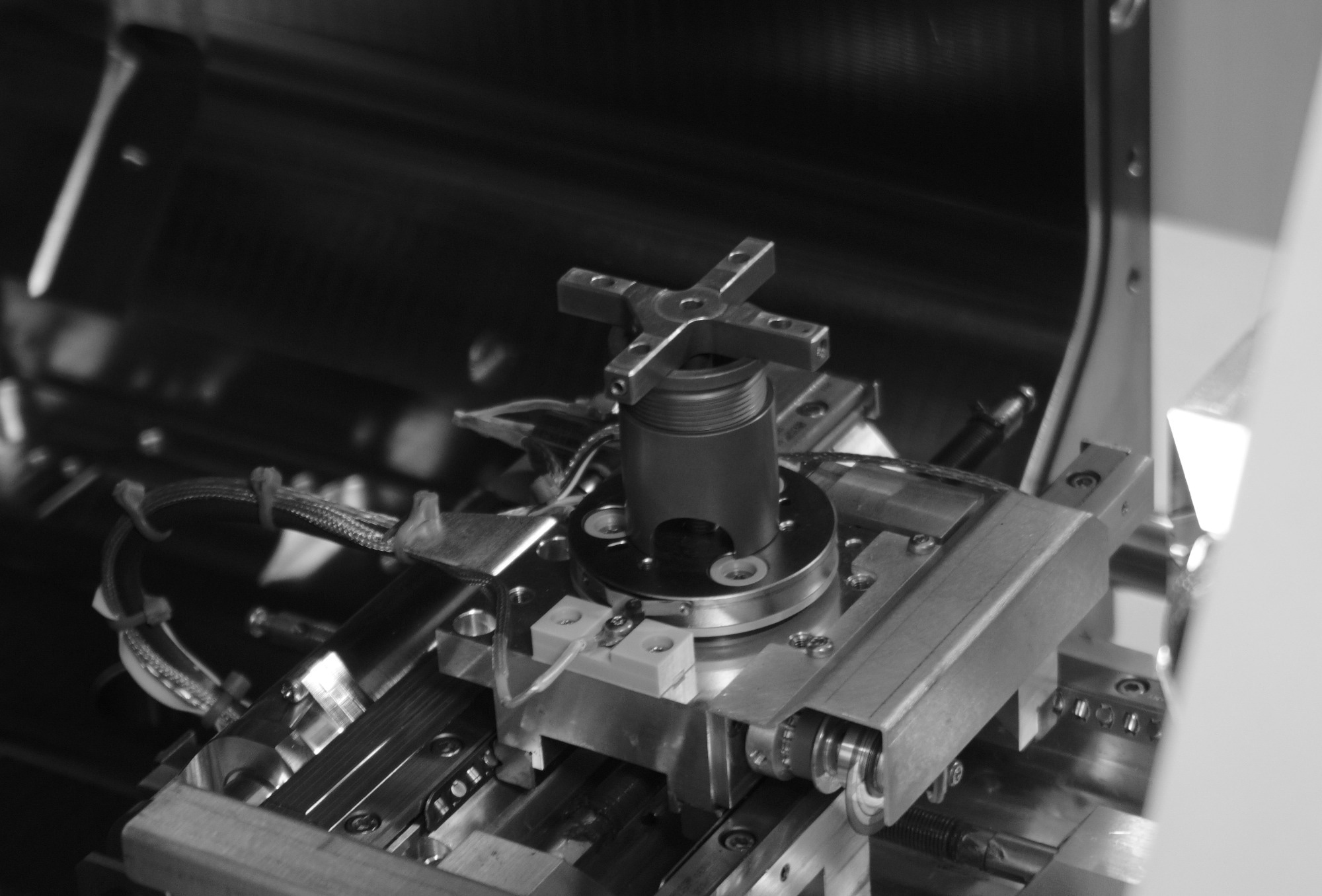

Image Credit: Thorium /UnSplash.com

Image Credit: Thorium /UnSplash.com

Multiphoton lithography (often called multiphoton 3D lithography) is an additive manufacturing approach for fabricating intricate micro- and nanostructures.

It relies on nonlinear optical absorption, most commonly two-photon (2PA) and three-photon absorption (3PA), to trigger highly localized chemical reactions inside a photosensitive resin. Because these reactions occur only at the laser focus, material can be written directly in three dimensions, rather than layer by layer.1

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

Defining lithography

Lithography, in its broadest sense, is the patterning of materials with light to generate structures whose size can range from the mesoscopic down to the nanoscale. Conventional optical lithographies rely on one-photon absorption (1PA), where a photon’s energy directly excites a photochemical transition across the absorber’s bandgap.

As 1PA occurs along the beam path and obeys Beer’s law, energy is deposited throughout the resist thickness; this limits true 3D fabrication and typically ties the smallest attainable features to the diffraction limit.2

In 2PA/3PA, the probability of absorption scales with the square or cube of the instantaneous intensity, so only the focal volume, where ultrafast pulses create sufficiently high peak intensity, undergoes the photochemical change.

This yields a spatially confined voxel that can be positioned arbitrarily in three dimensions, enabling direct write fabrication of free-form micro and nanostructures with features below 100 nm.2

How Multi-Photon Lithography (MPL) works

In a typical multiphoton lithography process, photoinitiator molecules absorb energy via 2PA or 3PA transitions from the ground state (S0) to an excited singlet state (S1). After intersystem crossing to the triplet state, reactive radicals are formed, initiating polymer crosslinking within the resist.

At higher laser intensities, additional mechanisms such as multiphoton ionization and avalanche ionization can also contribute to polymerization.1,3

The nonlinear nature of excitation is central to the technique’s appeal. Because reactions are confined to a sub-diffraction volume and governed by threshold behavior, neighboring voxels remain separate unless their combined exposure exceeds the polymerization threshold. This distinction underpins the difference between feature size and resolution, defined as the minimum separable pitch between features.

Researchers continue to push both limits using advanced optical strategies, such as 4π focusing and STED-inspired depletion, as well as chemical and materials engineering approaches designed to suppress proximity effects.3

Written in a serial, mask-free manner, multiphoton lithography enables genuinely free-form 3D architectures. It has become a platform technology across micro-optics and nanophotonics, nanomechanics and metamaterials, microfluidics, and bioengineering.

Sub-100-nm features are now routine, and printed polymer structures can be converted into ceramics, glass-ceramics, or metals through post-processing steps such as pyrolysis or calcination.2

Pushing the limits: diffraction, proximity effects, and LMC-MPL strategy

Despite its advantages, MPL faces two fundamental limits when pushing toward semiconductor-grade metrics: the optical diffraction barrier and the proximity effect.

The former arises from the long writing wavelength relative to the targeted feature, while the latter stems from radical diffusion/accumulation that blurs adjacent features when they are written in close spatial proximity.

As a result, the critical dimension (CD) and lateral resolution (LR) historically trailed those of e-beam and EUV lithography.4,5

Two complementary approaches have narrowed this gap. Light-confined MPL (LC-MPL) introduces a shaped inhibition (depletion) beam, inspired by stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, to suppress polymerization at the periphery of the excitation focus and thus beat the diffraction barrier.4

In parallel, matter confined MPL incorporates radical quenchers (e.g., TEMPO derivatives) into the resist, chemically suppressing polymerization tails and reducing proximity effects.

The most effective recent advance is to combine both, light and matter co confined MPL (LMC-MPL), which simultaneously limits the voxel’s optical and chemical extent. In a representative implementation, LMC-MPL achieves a 30 nm CD and 100 nm LR while maintaining robust 3D manufacturability and reliable pattern transfer.5

Chemistry of Quenching

The matter-confining effect of nitroxide quenchers such as TEMPO arises through three cooperative pathways: (1) static quenching via ground-state complexation with the initiator (evidenced by Stern–Volmer analysis and ESR behaviour), (2) dynamic quenching by energy/electron transfer from the excited initiator (shortened excited-state lifetimes), and (3) radical scavenging, whereby TEMPO rapidly reacts with propagating radicals to form non-reactive adducts.

Together, these routes compress the effective radical distribution, narrow lines, and mitigate proximity artifacts.

Case Studies:

Compound Micro-Optics Directly Printed on Image Sensors (the “Eagle-Eye” Lens)

MPL enables monolithic, on-chip micro-optics that would be difficult or impossible to assemble by conventional means. In a notable demonstration studied by Thiele et al., a compound microlens system for foveated imaging (“eagle-eye”) was directly printed and aligned onto a camera substrate, delivering complex optical functionality in a single contiguous print.

The ability to tune refractive index via exposure dose, to integrate refractive and diffractive elements, and to exploit true free-form surface shapes are central to this success.6

MPL micro-optics now also include fibre-end microendoscopes and broadband fibre-to-chip couplers fabricated with comparable ease. Further, Laser-grade optical elements can be printed directly and are able to withstand the high optical powers present within laser cavities.7-8

Bioengineered Scaffolds from Photosensitive Gelatin for Tissue Engineering

In biomedical research, multiphoton lithography is used to fabricate biopolymer scaffolds with precisely controlled porosity, strut thickness, and architectural anisotropy. Using photosensitive gelatin, researchers have produced CAD-designed three-dimensional scaffolds that support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.

By tuning lattice geometry, these structures decouple the intrinsic stiffness of the material from the stiffness experienced by cells, allowing more targeted control over cell fate while maintaining mechanical stability during culture and perfusion.9

Microrobots for Cell Delivery and Catalytic Microfluidics

MPL’s capacity to fabricate complex, hollow, and multi-material ready architectures enables functional microrobotics. In a recent case study by Hu et al., a hexahedral microrobot was printed by MPL and subsequently metallized (Ni/Ti) for magnetic actuation. The device operated as a mobile scaffold, transporting cells and demonstrating the feasibility of targeted cell delivery platforms.10

A related study by Zarzar et al. used MPL to fabricate intricate microfluidic chambers and flow geometries, which can then be coated with catalytic materials such as platinum to create efficient microscale reactors with precise spatial control.11

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

Multiphoton lithography has matured into a versatile platform for three-dimensional fabrication across nano-, micro-, and mesoscale regimes, particularly where precise architecture and material flexibility are required.

Advances in lasers, optomechanics, and automation (alongside nonlinear photophysical effects such as photo-thermal superlinearity and avalanche ionisation) are expanding the range of compatible materials and enabling true three-dimensional grayscale lithography with improved quality and throughput.

The central challenge is now how to combine free-form geometry, sub-100-nm resolution, functional materials, and practical manufacturing speeds without unacceptable trade-offs. Increasingly, data-driven control strategies, including deep learning, are being explored to optimise this balance and push the technique closer to its theoretical limits.

References and Further Readings

- Skliutas, E., et al. Multiphoton 3d Lithography. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2025, 5, 15.

- Skliutas, E., et al. Polymerization Mechanisms Initiated by Spatio-Temporally Confined Light. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 1211-1242.

- Paipulas, D.; Purlys, V., 4pi Multiphoton Polymerization. Applied Physics Letters 2020, 116, 031101.

- Gan, Z.; Cao, Y.; Evans, R. A.; Gu, M., Three-Dimensional Deep Sub-Diffraction Optical Beam Lithography with 9 Nm Feature Size. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 2061.

- Fischer, J.; Wegener, M., Three-Dimensional Optical Laser Lithography Beyond the Diffraction Limit. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2013, 7, 22-44.

- Thiele, S.; Arzenbacher, K.; Gissibl, T.; Giessen, H.; Herkommer, A. M., 3d-Printed Eagle Eye: Compound Microlens System for Foveated Imaging. Science Advances 2017, 3, e1602655.

- Li, J., et al. 3d-Printed Micro Lens-in-Lens for in Vivo Multimodal Microendoscopy. Small 2022, 18, 2107032.

- Angstenberger, S.; Ruchka, P.; Hentschel, M.; Steinle, T.; Giessen, H., Hybrid Fiber–Solid-State Laser with 3d-Printed Intracavity Lenses. Optics Letters 2023, 48, 6549-6552.

- Ovsianikov, A.; Deiwick, A.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Möller, L.; Dra¨ger, G.; Chichkov, B., Laser Fabrication of Three-Dimensional CAD Scaffolds from Photosensitive Gelatin for Applications in Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 851-858.

- Hu, N. et al. Development of 3d-Printed Magnetic Micro-Nanorobots for Targeted Therapeutics: The State of Art. Advanced NanoBiomed Research 2023, 3, 2300018.

- Zarzar, L. D., et al. Multiphoton Lithography of Nanocrystalline Platinum and Palladium for Site-Specific Catalysis in 3d Microenvironments. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 4007-4010.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.