After more than 25 years of intensive research, nanofibers remain scientifically promising but industrially constrained, according to a new perspective published in Frontiers in Nanotechnology.

Image Credit: Faktors/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Faktors/Shutterstock.com

The study examines why polymeric and inorganic nanofibers, explored in applications ranging from filtration to medicine, have yet to achieve widespread commercial adoption.

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

Across synthetic chemistry and materials science, researchers have developed an array of nanomaterials, including nanosheets, nanopowders, nanotubes, and nanofibers.

While laboratory studies have demonstrated impressive properties, only a small fraction of these materials has transitioned into real products.

The authors argue that commercial success typically requires meeting at least two of three conditions: reproducible industrial-scale production, competitive cost or clear performance advantages, and sufficient stability or lifetime.

Nanofibers remain one of the few nanomaterial classes that could meet all three - at least in certain applications.

Spinning Nanofibers at Scale

The review focuses on two dominant production methods: electrospinning and centrifugal spinning. Electrospinning has fine control over fiber diameter but suffers from low throughput and high operational complexity.

Centrifugal spinning, driven by mechanical rotation rather than electric fields, has much higher production rates but introduces challenges in process control and uniformity.

Although both techniques can produce high-quality nanofibers, scaling them reliably remains difficult. Controlling airflow, solvent evaporation, fiber collection, and defect formation requires detailed engineering expertise that often exceeds what companies can justify for emerging materials.

Solvents are a Major Barrier to Success

The most significant barrier, the authors argue, is the polymer-solvent system. Many widely used polymers, such as polyamide 6 and polyacrylonitrile, require toxic and costly organic solvents. Water-soluble polymers are cheaper and safer, but their instability in aqueous environments limits their use in many applications.

The economics are stark: producing one kilogram of nanofibers from a 10 wt% polymer solution can waste roughly nine kilograms of solvent through evaporation.

Developing entirely new solvents and solvent systems is seen as unrealistic, leaving solvent recovery as the most viable long-term solution. Closed-loop systems, solvent condensation, and adsorption-based recovery methods are technically feasible but remain rare due to cost and complexity.

Designed Stability or Degradability

Nanofiber stability depends strongly on its application. Filtration membranes require long-term durability, whereas biomedical applications, such as wound healing or tissue scaffolds, can benefit from controlled degradation.

To bridge this gap, the authors highlight post-processing strategies including cross-linking, plasma treatment, and the application of ultrathin inorganic coatings using techniques such as Atomic Layer Deposition or Vapour Phase Infiltration.

These approaches can significantly enhance mechanical strength and chemical resistance, while also enabling additional functions such as antibacterial activity or controlled drug release.

Safety and Industry Caution

Nanofibers also face a perception problem. Historical concerns around asbestos have made industry cautious about fibrous materials.

However, recent toxicological studies suggest that inorganic nanofibers are generally no more hazardous than nanoparticles of the same materials - and may be less so - because their larger size limits penetration into the skin or lungs.

Biopolymeric nanofibers are widely considered safe due to biodegradation, though the biological effects of their degradation products remain incompletely understood. The authors argue that continued toxicological research is essential to building confidence among manufacturers and regulators.

Where Nanofibers Are Working

Despite these challenges, nanofibers have achieved commercial success in filtration. Nanofiber membranes are widely used in air and liquid filtration systems, reaching the highest levels of technological readiness.

Other sectors, like cosmetics, sorbents, and niche biomedical products, are progressing more slowly but show strong potential where performance advantages justify higher production costs and complexity.

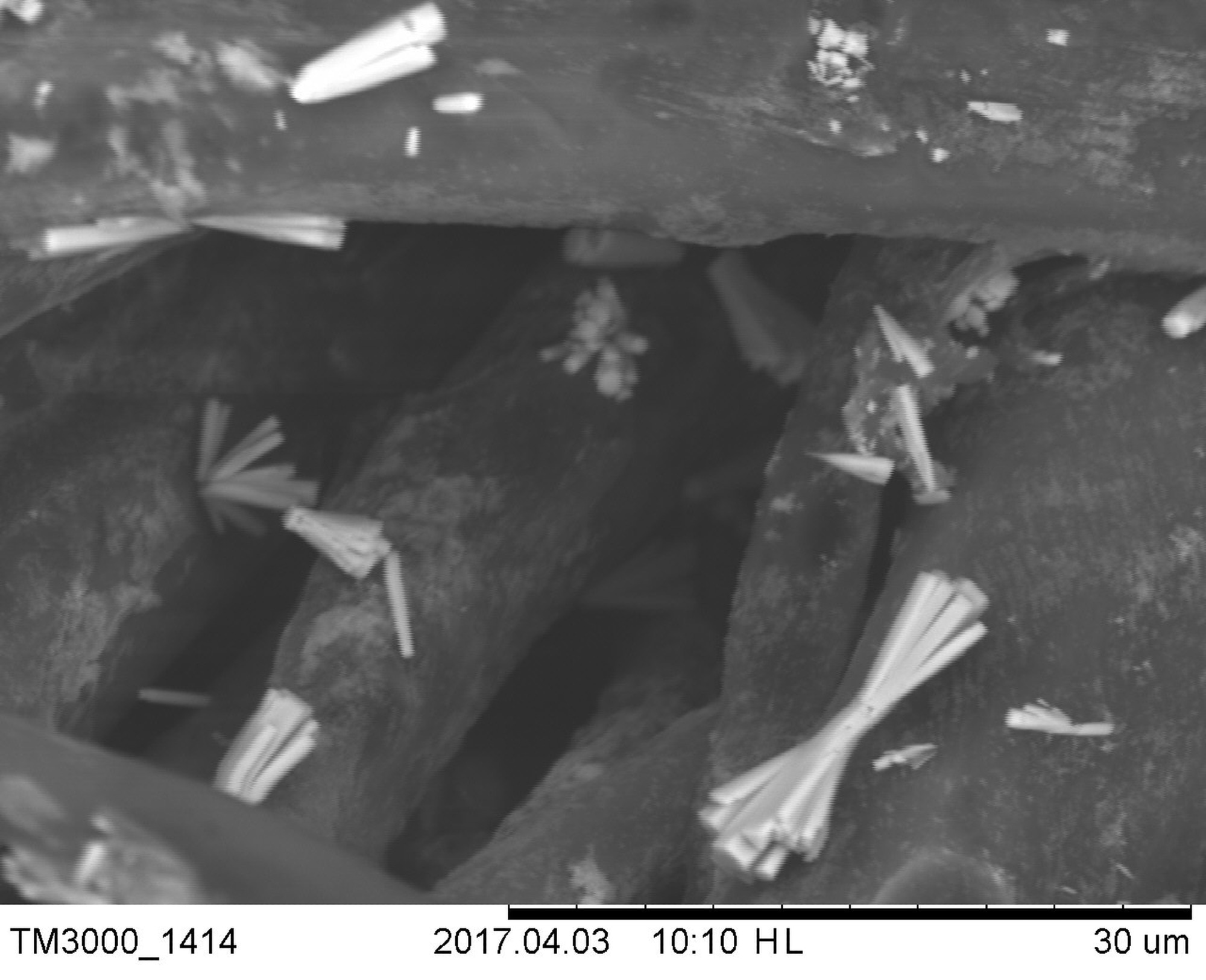

Conversely, inorganic nanofibers for catalysis and energy applications remain limited by high processing costs and batch-based manufacturing steps.

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

What is the Future of Nanofibers

The authors caution against expecting rapid breakthroughs. Instead, they call for steady, system-level improvements: higher productivity, better process control, solvent recovery, and closer collaboration between academia and industry.

These challenges, the authors note, are not unique to nanofibers but reflect broader issues facing the advanced materials manufacturing sector. Progress is likely to be incremental, application-specific, and driven by clear performance gains rather than scientific novelty alone.

Nanofibers still have much to offer - but only when industrial realities are addressed as rigorously as laboratory science.

Journal Reference

Hromadko L., et al. (2025). Nanofibers: where they are, where we need them to be. Frontiers in Nanotechnology 7:1706183. DOI: 10.3389/fnano.2025.1706183