From ultrafast electronics to regenerative medicine, 1D nanomaterials are an integral aspect of the "nanoscale revolution". But their true impact will be unlocked when we can reliably assemble, align, and integrate them into large-area architectures.1

Image Credit: Zagach Letters/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Zagach Letters/Shutterstock.com

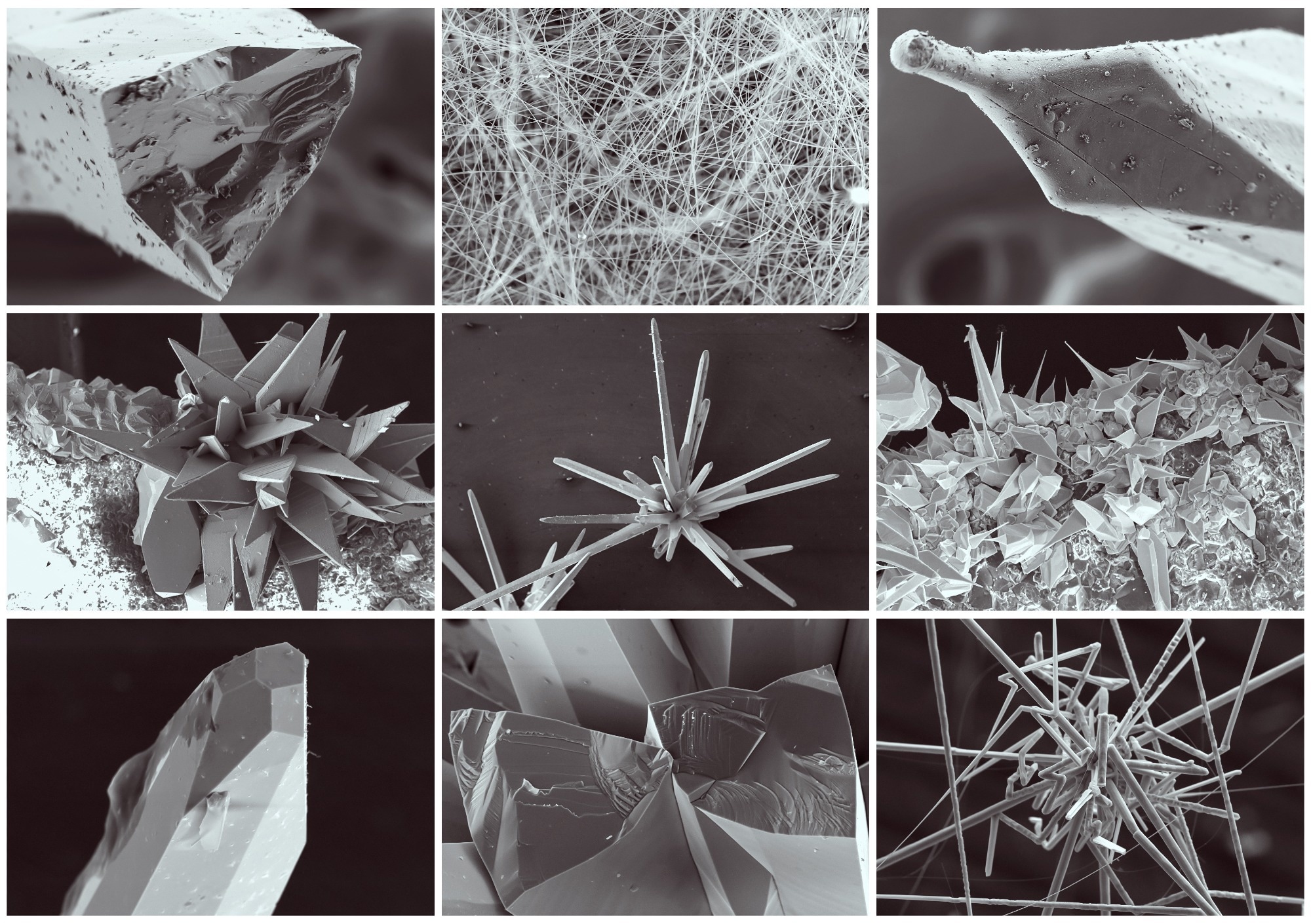

One-dimensional (1D) nanomaterials are structures in which two dimensions are confined to the nanometer scale (1 to 100 nm), while the third dimension is much larger, resulting in wire-, ribbon-, or tube-like morphologies.

This geometry leads to unique, highly directional electrical, thermal, and optical properties that are markedly different from their bulk counterparts.1

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

Dimensionality: from 0D to 3D

Dimensionality describes how many directions in a nanomaterial are confined to the nanoscale. In 0D nanomaterials (e.g., quantum dots), all three dimensions are below ~100 nm, giving full confinement and strongly size-dependent properties.

In 1D nanomaterials, two dimensions are at the nanoscale, while the third is not, resulting in structures such as carbon nanotubes.2 In 2D nanomaterials, such as graphene, only one dimension exists at the nanoscale.

In 3D nanostructured materials, nanoscale features exist in all directions, yet the overall object (for example, porous foams) is still macroscopic.2

Compared with 0D and 2D systems, 1D nanomaterials occupy an intermediate regime: they preserve strong confinement and large surface area in the radial direction, yet support long-range, almost bulk-like transport along the axis.

This combination is particularly advantageous whenever directional conduction or guidance is needed, for example, in interconnects, waveguides, and aligned biological scaffolds.2

Common Types of 1D Nanomaterials

Although chemistries and fabrication routes vary widely, several structural motifs appear repeatedly:

Nanowires

Nanowires are solid filaments with diameters from as little as one or two nanometers to hundreds, and their lengths can often exceed tens of micrometres.

They can be grown from the vapor phase, for instance, via the vapor–liquid–solid mechanism, or synthesized solution-wise. Semiconductor nanowires based on Si, Ge, GaAs, InP, and GaN, as well as oxide and metallic nanowires, have been exploited as nanoscale transistors, light emitters, sensors, and interconnects.1

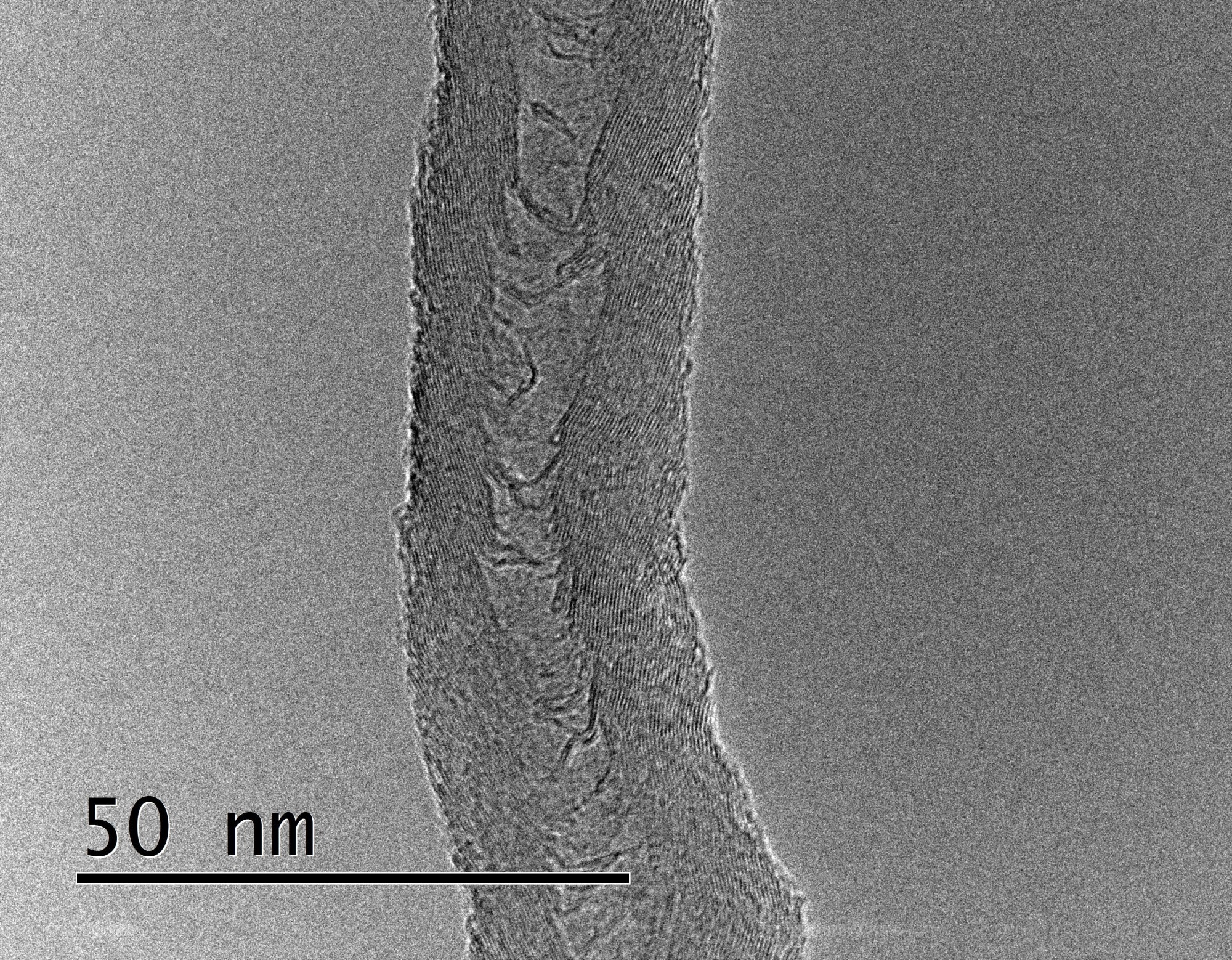

Nanotubes

Image Credit: Daniel Ramirez-Gonzalez/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Daniel Ramirez-Gonzalez/Shutterstock.com

Nanotubes are hollow 1D structures with material concentrated in a cylindrical wall.

Beyond carbon nanotubes, inorganic nanotubes such as TiO2, ZnO, and layered dichalcogenides form a rich family. TiO2 nanotubes are frequently fabricated by self-organized anodic oxidation of titanium, and often exhibit uniform diameters, controlled lengths, and vertical alignment, making them attractive for photoelectrochemical devices, photocatalysis, and electrochemical energy storage.3

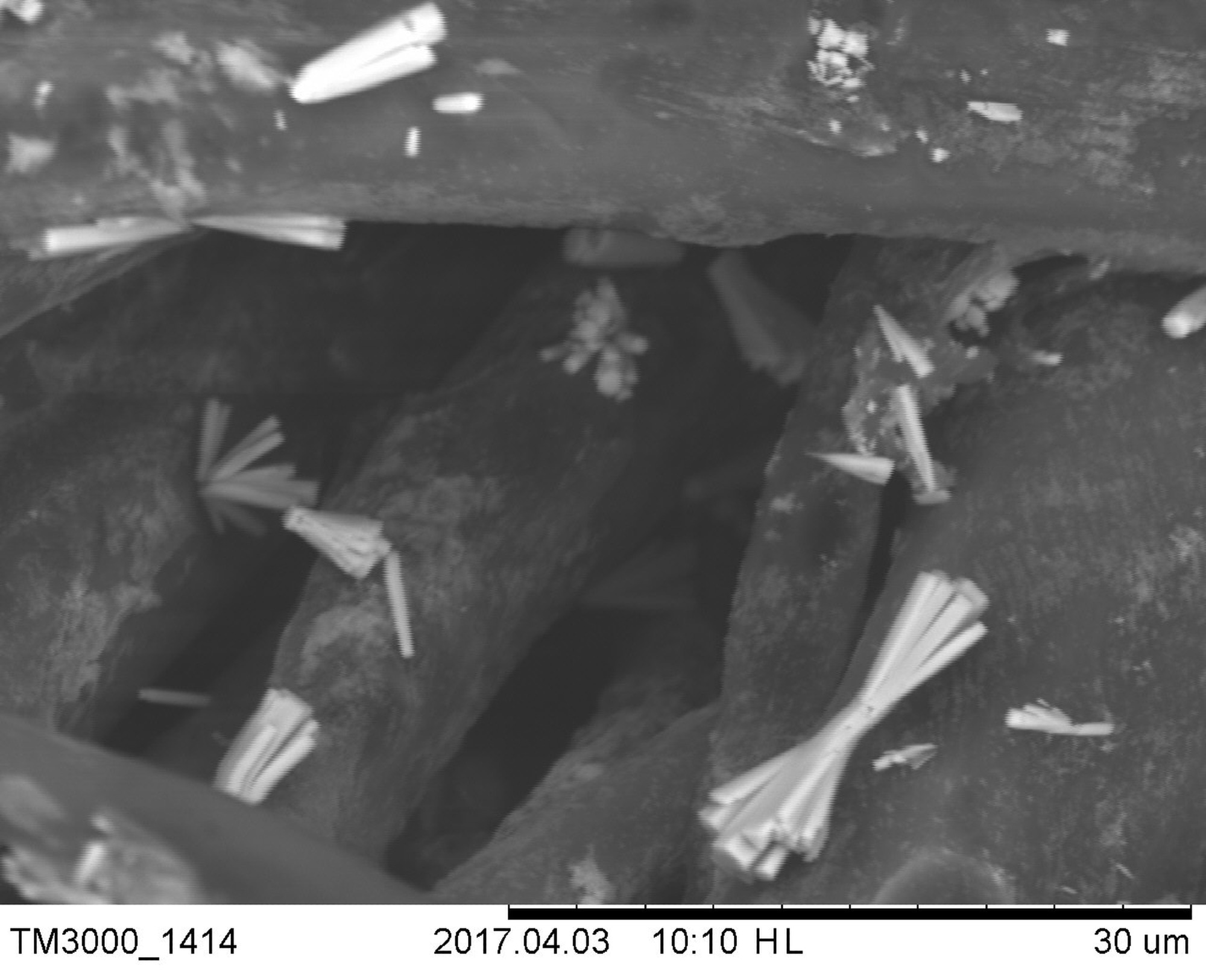

Nanorods and nanofibers

Image Credit: Faktors/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Faktors/Shutterstock.com

Nanorods are short, elongated crystals, often obtained in solution with shape-directing ligands. Nanofibers typically denote longer, flexible filaments generated by electrospinning polymers, ceramics, or composites.

Electrospun oxide, carbon and polymer nanofibers combine high surface area with tunable porosity and mechanical strength, and are widely used in filtration, catalysis, batteries and tissue engineering.4

Topological and complex 1D architectures

More recent advances include 1D nanomaterials based on topological insulators or semimetals, as well as core-shell or hollow-porous architectures.

Thermomechanical epitaxy, for example, can produce wafer-scale arrays of single-crystal topological nanowires with extremely high aspect ratios, opening possibilities in quantum transport and spintronics.5

Properties and Applications of 1D Nanomaterials

The utility of 1D nanomaterials arises from a set of distinctive properties that translate directly into a range of diverse applications.

Their high aspect ratio leads to anisotropic transport, providing efficient pathways for charge and heat along the axis while transverse transport is confined; as a result, single-crystal nanowires can serve as near-ideal conduction channels in high-mobility transistors, nanoscale interconnects, and thermoelectric elements.1

Their large specific surface area enhances catalysis, adsorption, and interfacial charge transfer, which is particularly valuable in energy devices where nanowire, nanotube, and nanofiber electrodes improve reaction kinetics and enable rapid ion insertion in batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells.1

Radial confinement and strong light-matter interaction give 1D nanomaterials a tailorable optical response, allowing semiconductor nanowires to act as optical resonators or waveguides in nanoscale lasers, photodetectors, and solar cells, with axial or radial compositional grading enabling band-gap engineering within a single structure.6

Many 1D nanomaterials also combine mechanical flexibility with high tensile strength, so that networks of nanowires, nanotubes, or nanofibers form compliant, electrically functional films for flexible electronics and stretchable sensors.

Their elongated morphology closely mimics the fibrous extracellular matrix, and aligned nanofiber scaffolds can guide cell orientation, migration and differentiation in biomedical applications, especially when their surfaces are functionalized with peptides, growth factors or drugs to add biochemical cues.4

Finally, for magnetic or high-permittivity compositions, the 1D geometry enhances interfacial polarization and magnetic anisotropy, which is crucial for electromagnetic interference shielding and microwave absorption, where impedance matching and multiple scattering in complex 1D networks enable efficient broadband attenuation.7

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

How 1D nanomaterials are advancing science?

Beyond their established uses, 1D nanomaterials are enabling advances in several frontiers.

For example, in nerve tissue engineering and spinal cord repair, Shi et al. report that aligned nanofiber scaffolds create a biomimetic environment that guides neurite extension and axonal regeneration.

By tailoring fiber diameter, alignment, and surface chemistry, they can modulate neuronal adhesion, polarity, and synapse formation, while integrating conductive nanowires or nanotubes allows local electrical stimulation that further promotes neurite outgrowth and functional recovery. Here, 1D nanomaterials act as active regulators of cell behaviour and tissue organization rather than merely passive supports.8

In a very different context, Wang et al. review how 1D nanostructures such as nanotubes, nanowires, and nanofibers underpin lightweight, high-performance microwave absorbers for electromagnetic protection.

Their anisotropic geometry and hierarchical porosity enhance multiple reflections and interfacial polarization, and combining dielectric and magnetic components enables precise tuning of impedance matching and loss mechanisms.7

Consequently, thin coatings based on complex 1D architectures can strongly attenuate incident microwaves over broad frequency ranges, addressing key challenges in electromagnetic interference mitigation and stealth technologies.7

Image Credit: /Shutterstock.com

1D nanomaterials are best viewed as a versatile platform, rather than a single class of objects. Defined by their nanoscale dimensions, they sit between 0D, 2D, and 3D nanomaterials in terms of confinement and transport, yet combine desirable elements of all three: Strong surface and quantum effects, efficient directional conduction, and the ability to assemble into macroscopic structures.

References and Further Readings

- Garnett, E.; Mai, L.; Yang, P., Introduction: 1d Nanomaterials/Nanowires. Chemical reviews 2019, 119, 8955-8957.

- Roy, D.; Srivastava, A. K.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Namburi, E. P., 0d, 1d, 2d & 3d Nano Materials: Synthesis and Applications. In Novel Defence Functional and Engineering Materials (Ndfem) Volume 1: Functional Materials for Defence Applications, Springer: 2024; pp 73-91.

- Lee, K.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P., One-Dimensional Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials: Nanotubes. Chemical reviews 2014, 114, 9385-9454.

- Machín, A.; Fontánez, K.; Arango, J. C.; Ortiz, D.; De León, J.; Pinilla, S.; Nicolosi, V.; Petrescu, F. I.; Morant, C.; Márquez, F., One-Dimensional (1d) Nanostructured Materials for Energy Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 2609.

- Liu, N.; Yang, Y.-X.; Lu, C.; Kube, S. A.; Raj, A.; Sohn, S.; Zhang, X.; Costa, M. B.; Liu, Z.; Schroers, J., Realizing One-Dimensional Single-Crystalline Topological Nanomaterials through Thermomechanical Epitaxy. Matter 2025.

- Choudhary, M.; Shukla, S. K.; Kumar, V.; Govender, P. P.; Wang, R.; Hussain, C. M.; Mangla, B., 1d Nanomaterials and Their Optoelectronic Applications. In Nanomaterials for Optoelectronic Applications, Apple Academic Press: 2021; pp 105-123.

- Wang, Y.-f.; Zhu, L.; Han, L.; Zhou, X.-h.; Gao, Y.; Lv, L.-h., Recent Progress of One-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Microwave Absorption: A Review. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 7107-7122.

- Shi, B.; Lu, S.; Yang, H.; Mahmood, S.; Sun, C.; Malek, N. A. N. N.; Kamaruddin, W. H. A.; Saidin, S.; Zhang, C., One-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Nerve Tissue Engineering to Repair Spinal Cord Injury. BMEMat 2025, 3, e12111.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.