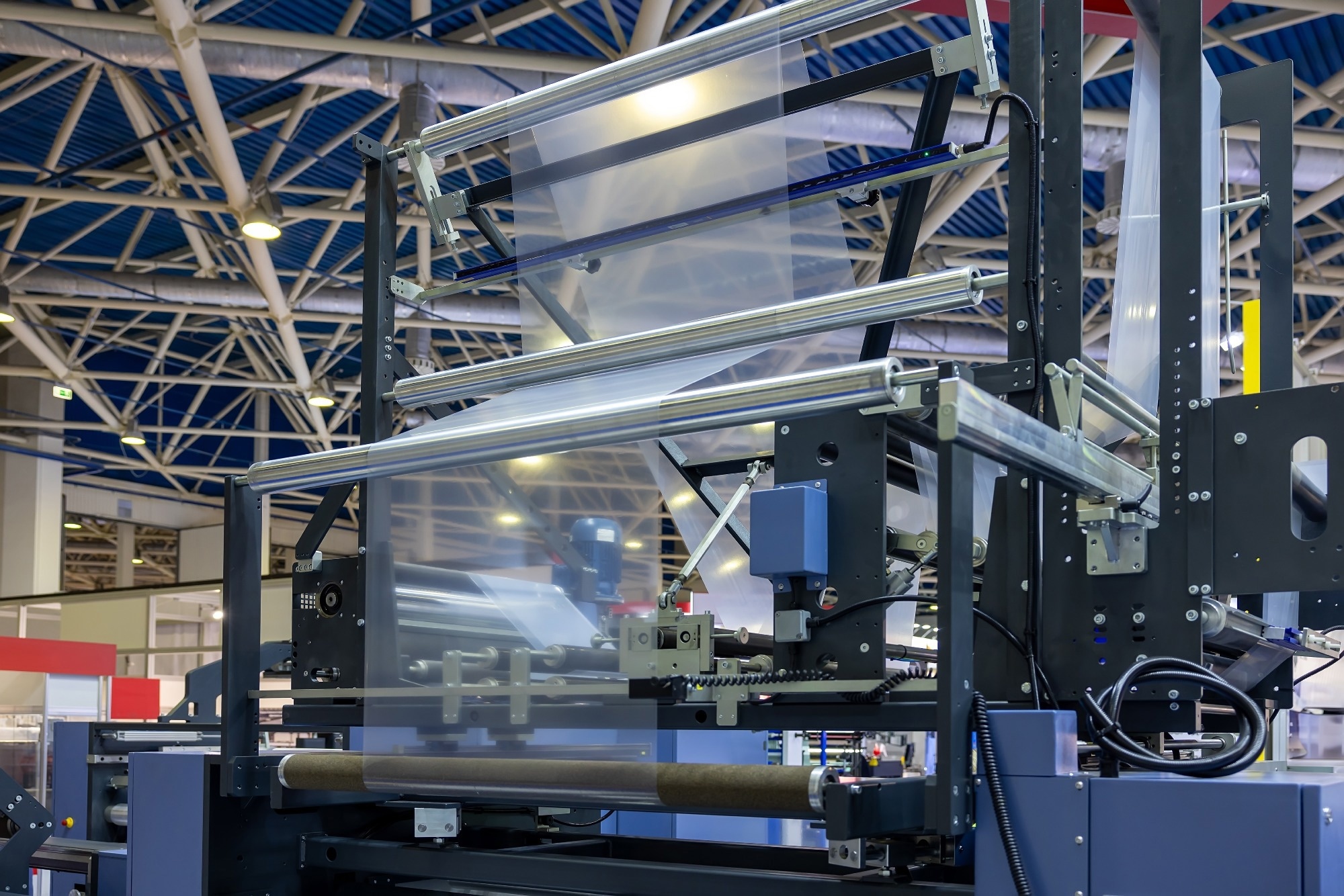

With a little engineering, clear plastics become programmable. By embedding nanoscale structures in PMMA, polycarbonate, and more, they can deliver glass-like clarity, plus impact resistance, weatherability, and tailored transmission or emission.

Image Credit: Koff-m/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Koff-m/Shutterstock.com

Everything comes down to managing dispersion, interfaces, and refractive-index matching. The trick is staying below the scattering limit. When features are smaller than visible wavelengths and refractive-index contrast is controlled, you can add structure without sacrificing clarity.1

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

In most filled plastics, mismatches between micron-scale particles and refractive index can cause strong scattering. This shows up on a macroscopic scale as haze and loss of transmittance. When you bring characteristic dimensions of heterogeneities down below the wavelength of visible light (typically below 50-100 nm), scattering drops dramatically, and the material can remain optically clear even if its internal morphology is uneven.2

For engineering plastics, this opens three key design routes:

- Dispersing nanofillers (platelets, rods, or particles) that are small enough and index-matched enough to avoid haze while adding mechanical, barrier, or thermal functions.

- Designing block copolymers or blends that microphase-separate into nanometer-scale morphologies, toughening the matrix without the coarse rubber domains used in traditional impact modifiers.

- Incorporating optically active nanocrystals to deliberately tune transmission, reflection, or emission, while controlling feature sizes to preserve transparency.1-2

The central challenge is controlling dispersion, interfacial chemistry, and refractive index so that optical losses are minimized while the desired mechanical and functional improvements are realized.

Nanofillers in PMMA, Polycarbonate, and COC

Nanofiller-modified transparent polymers are the most direct form of optical nanostructuring. This involves embedding nanoscale objects inside a clear matrix.

In PMMA, Jamaluddin et al. used cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) to produce nanocomposite films with high visible transmittance and improved tensile strength and toughness. At low loadings (≈1 wt%) and with appropriate surface modification, CNFs can remain well dispersed. Under these conditions, the composites stay smooth and transparent, with low haze, while mechanical performance increases.3

Researchers have reported similar approaches using inorganic nanofillers, such as boron nitride nanosheets and silica, to achieve UV shielding, thermal management, or scratch resistance. Optical clarity remains conditional. Lateral dimensions must stay small, and refractive indices must remain close to that of PMMA.

When particle size or agglomerates drift into the sub-micron range, scattering rises sharply. This is why processing and surface treatment often matter as much as the choice of filler.4

Polycarbonate and PMMA blends provide another route in which the nanostructure is the phase morphology of the two polymers. Under high shear or with reactive compatibilization, PC/PMMA blends create nanostructured domains.

These domains boost toughness and heat resistance, all while maintaining high transparency. This depends on domain sizes staying well below the wavelength of visible light. The refractive indices must also be closely matched.5

Cyclic olefin copolymers (COCs) are already valued for their low birefringence, high transparency, and low water uptake – particularly in optical and microfluidic components.

They can be blended with other polymers for toughness, provided the partner polymer’s refractive index is closely matched. This typically means within 0.03-0.05, so that even if phase separation occurs, scattering remains low.6

At the same time, COCs can host optically active nanoparticles such as CdSe/ZnS quantum dots. This results in luminescent films that work well with methods such as spin coating or nanoimprint lithography, with minimal loss of clarity.6

Microphase-Separated and Nanocellular Architectures

Image Credit: hodim/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: hodim/Shutterstock.com

Microphase separation is one way to strengthen transparent plastics without introducing large light-scattering domains.

Cho et al. show how photopolymerization-induced microphase separation can form bicontinuous structures in PMMA-based block copolymers. The morphology consists of glassy PMMA and rubbery, crosslinked domains, with length scales in the tens of nanometers.1

Similarly, Lee et al. demonstrated a related system in which PMMA blocks are covalently linked to a soft poly(n-butyl acrylate-co-EGDA) network. As polymerization proceeds, increasing incompatibility drives microphase separation, and crosslinking stabilizes the resulting nanostructure.7

The resulting material exhibits high impact resistance and dimensional stability at elevated temperature, yet maintains visible transmittance above 88 % with negligible haze, even when heated, because the phase domains are too small to scatter visible light efficiently.7

Nanocellular PMMA offers another route where the dispersed phase is not a second polymer but a gas. By carefully tuning foaming conditions, cell sizes can be driven into the sub-100-nm regime and cell densities increased to the point where the foam appears macroscopically transparent.8

This enables lightweight, clear panels or lenses with lower density, a tunable refractive index, and still-useful mechanical performance.8

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

Controlling Haze and Light Management

Haze in transparent plastics mainly comes from forward scattering. Too much and the plastic becomes milky. This frosted appearance is undesirable in many optical components but useful in light diffusers. Nanostructuring gives engineers a handle on both suppressing and exploiting haze by controlling feature size, refractive index contrast, and spatial distribution.1, 9

Transparent electrodes provide a clear example of how nanoscale geometry can preserve optics.

Menamparambath et al. used ~20 nm silver nanowires decorated with ~5 nm nanoparticles to produce films with >96 % transmittance, ~1 % haze, and low sheet resistance. Small diameters reduce scattering, while high aspect ratios enable electrical percolation at low coverage. This combination keeps optical losses low.10

Similar principles translate to polymer-based transparent conductors or antistatic layers where metal nanowires, graphene flakes, or other conductive nanostructures are embedded in a plastic matrix.

In laminates and clear polymer armour, multilayer stacks of polycarbonate or PMMA are used. They limit crack spreading. These layers also reduce scattering from internal reflections and damage-related microfeatures.2

There is a general trend in research towards tougher stacks. Here, the reinforcing phases stay below the optical resolution limit. They are also matched in index to keep haze low until impact occurs.2

On the light-management side, sub-wavelength nanostructures on or within transparent plastics are being used to create anti-reflection surfaces, angularly selective filters, or near-infrared shielding films.11

Hybrid foils with anisotropic nanoscale pigments and magnetic nanoparticles can provide high visible transparency with strong near-infrared blocking and low haze. This enables thermal management glazing that remains visually clear.

Oxide/metal/oxide stacks and nanotextured interfaces can also reduce wide-angle scattering while maintaining high transmittance and electrical conductivity.11-12

From Optical Plastic to Engineered Photonic Media

The future of clear plastics is changing. These materials are moving from passive substrates to active, engineered optical media.

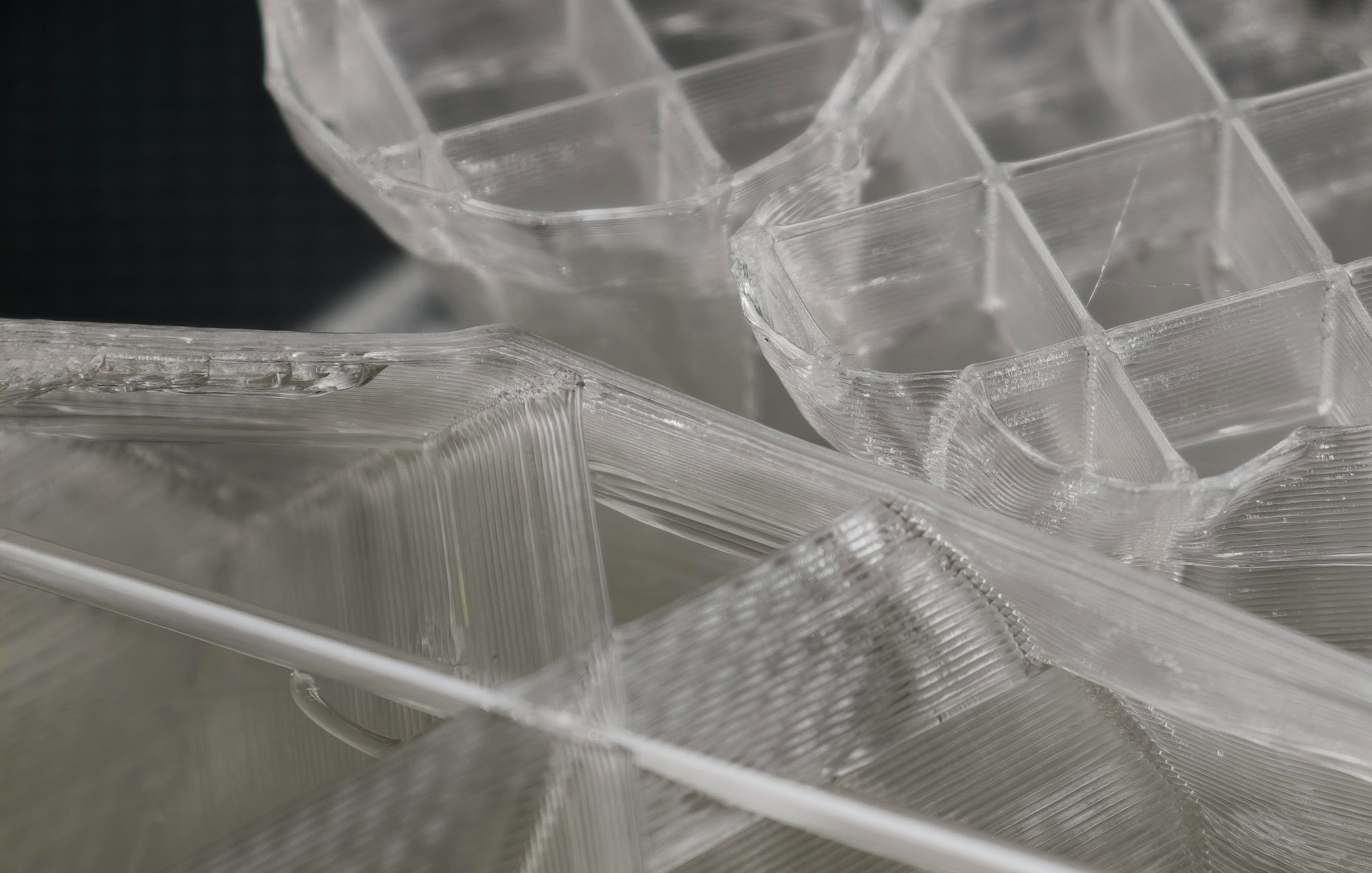

Luminescent COC films with semiconductor nanocrystals already offer tunable emission, while nanostructured, 3D-printable PMMA block copolymers show that toughness, thermal stability, and optical clarity can coexist in a single resin.1

At the same time, the general design rules emerging from transparent polymer nanocomposite studies are broadly applicable: keep structural features deeply sub-wavelength, minimize refractive index contrast between phases when transparency is desired, and use interfacial chemistry to control dispersion and microphase separation.11

For materials engineers, this shifts the focus from simply choosing a clear polymer to designing multiscale structures that define how light and mechanical forces traverse the material.

References and Further Readings

- Cho, S. et al. Impact-resistant, haze-free, 3D-printable transparent block copolymer resin via photopolymerization-induced microphase separation. NPG Asia Materials 2025, 17 (1), 37.

- Loste, J. et al. Transparent polymer nanocomposites: An overview on their synthesis and advanced properties. Progress in Polymer Science 2019, 89, 133-158. DOI: -

- Jamaluddin, N.; Hsu, Y.-I.; Asoh, T.-A.; Uyama, H. Optically transparent and toughened poly(methyl methacrylate) composite films with acylated cellulose nanofibers. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (16), 10752-10758.

- Bisht, A.; Kumar, V.; Maity, P. C.; Lahiri, I.; Lahiri, D. Strong and transparent PMMA sheet reinforced with amine functionalized BN nanoflakes for UV-shielding application. Composites Part B: Engineering 2019, 176, 107274. DOI:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107274

- Bubmann, T.; Seidel, A.; Ruckdäschel, H.; Altstädt, V. Transparent PC/PMMA blends with enhanced mechanical properties via reactive compounding of functionalized polymers. Polymers 2021, 14 (1), 73. DOI:10.3390/polym14010073, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/1/73

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Jian, Z. Cyclic olefin terpolymers with high refractive index and high optical transparency. ACS Macro Letters 2023, 12 (3), 395-400. DOI: -

- Lee, K.; Corrigan, N.; Boyer, C. Polymerization induced microphase separation for the fabrication of nanostructured materials. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2023, 62 (44), e202307329. DOI:10.1002/anie.202307329, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.202307329

- Bernardo, V.; Martin-de Leon, J.; Pinto, J.; Catelani, T.; Athanassiou, A.; Rodriguez-Perez, M. A. Low-density PMMA/MAM nanocellular polymers using low MAM contents: Production and characterization. Polymer 2019, 163, 115-124.

- Lee, H. J.; Kim, B. H.; Takaloo, A. V.; Son, K. R.; Dongale, T. D.; Lim, K. M.; Kim, T. G. Haze-Suppressed Transparent Electrodes Using IZO/Ag/IZO Nanomesh for Highly Flexible and Efficient Blue Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Advanced Optical Materials 2021, 9 (15), 2002010. DOI:10.1002/adom.202002010, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adom.202002010

- Menamparambath, M. M.; Muhammed Ajmal, C.; Kim, K. H.; Yang, D.; Roh, J.; Park, H. C.; Kwak, C.; Choi, J.-Y.; Baik, S. Silver nanowires decorated with silver nanoparticles for low-haze flexible transparent conductive films. Scientific Reports 2015, 5 (1), 16371. DOI:10.1038/srep16371, https://www.nature.com/articles/srep16371

- Bhatti, M. R. A.; Gupta, J.; Gnanadass, S.; Robinson, C. J.; Peijs, T. Development of Transparent Polymer Armour based on High Strength Polyethylene Films. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2025.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, N.; Xin, Y.; Cao, X.; Ji, S.; Jin, P. CsxWO3 nanoparticle-based organic polymer transparent foils: low haze, high near infrared-shielding ability and excellent photochromic stability. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2017, 5 (25), 6251-6258.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.