Nov 15 2012

The heart of the computer industry is known as "Silicon Valley" for a reason. Integrated circuit computer chips have been made from silicon since computing's infancy in the 1960s. Now, thanks to a team of USC researchers, carbon nanotubes may emerge as a contender to silicon's throne.

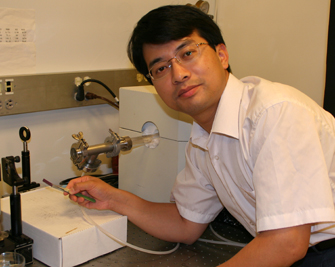

Chongwu Zhou holds up a piece of plastic substrate used to build nanoscale transistors and circuits.

Chongwu Zhou holds up a piece of plastic substrate used to build nanoscale transistors and circuits.

Scientists and industry experts have long speculated that carbon nanotube transistors would one day replace their silicon predecessors. In 1998, Delft University built the world's first carbon nanotube transistors – carbon nanotubes have the potential to be far smaller, faster, and consume less power than silicon transistors.

A key reason carbon nanotubes are not in your computer right now is that they are difficult to manufacture in a predictable way. Scientists have had a difficult time controlling the manufacture of nanotubes to the correct diameter, type and ultimately chirality, factors that control nanotubes' electrical and mechanical properties.

Think of chirality like this: if you took a sheet of notebook paper and rolled it straight up into a tube, it would have a certain chirality. If you rolled that same sheet up at an angle, it would have a different chirality. In this example, the notebook paper represents a sheet of latticed carbon atoms that are rolled-up to create a nanotube.

A team led by Professor Chongwu Zhou of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and Ming Zheng of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Maryland solved the problem by inventing a system that consistently produces carbon nanotubes of a predictable diameter and chirality.

Zhou worked with his group members Jia Liu, Chuan Wang, Bilu Liu, Liang Chen, and Ming Zheng and Xiaomin Tu of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Maryland.

"Controlling the chirality of carbon nanotubes has been a dream for many researchers. Now the dream has come true." said Zhou. The team has already patented its innovation, and its research will be published Nov. 13 in Nature Communications.

Carbon nanotubes are typically grown using a chemical vapor deposition (CVD) system in which a chemical-laced gas is pumped into a chamber containing substrates with metal catalyst nanoparticles, upon which the nanotubes grow. It is generally believed that the diameters of the nanotubes are determined by the size of the catalytic metal nanoparticles. However, attempts to control the catalysts in hopes of achieving chirality-controlled nanotube growth have not been successful.

The USC team's innovation was to jettison the catalyst and instead plant pieces of carbon nanotubes that have been separated and pre-selected based on chirality, using a nanotube separation technique developed and perfected by Zheng and his coworkers at NIST. Using those pieces as seeds, the team used chemical vapor deposition to extend the seeds to get much longer nanotubes, which were shown to have the same chirality as the seeds..

The process is referred to as "nanotube cloning." The next steps in the research will be to carefully study the mechanism of the nanotube growth in this system, to scale up the cloning process to get large quantities of chirality-controlled nanotubes, and to use those nanotubes for electronic applications.