A new optofluidic approach to three-dimensional micro- and nanofabrication allows a wide range of materials to be assembled into complex, functional microdevices.

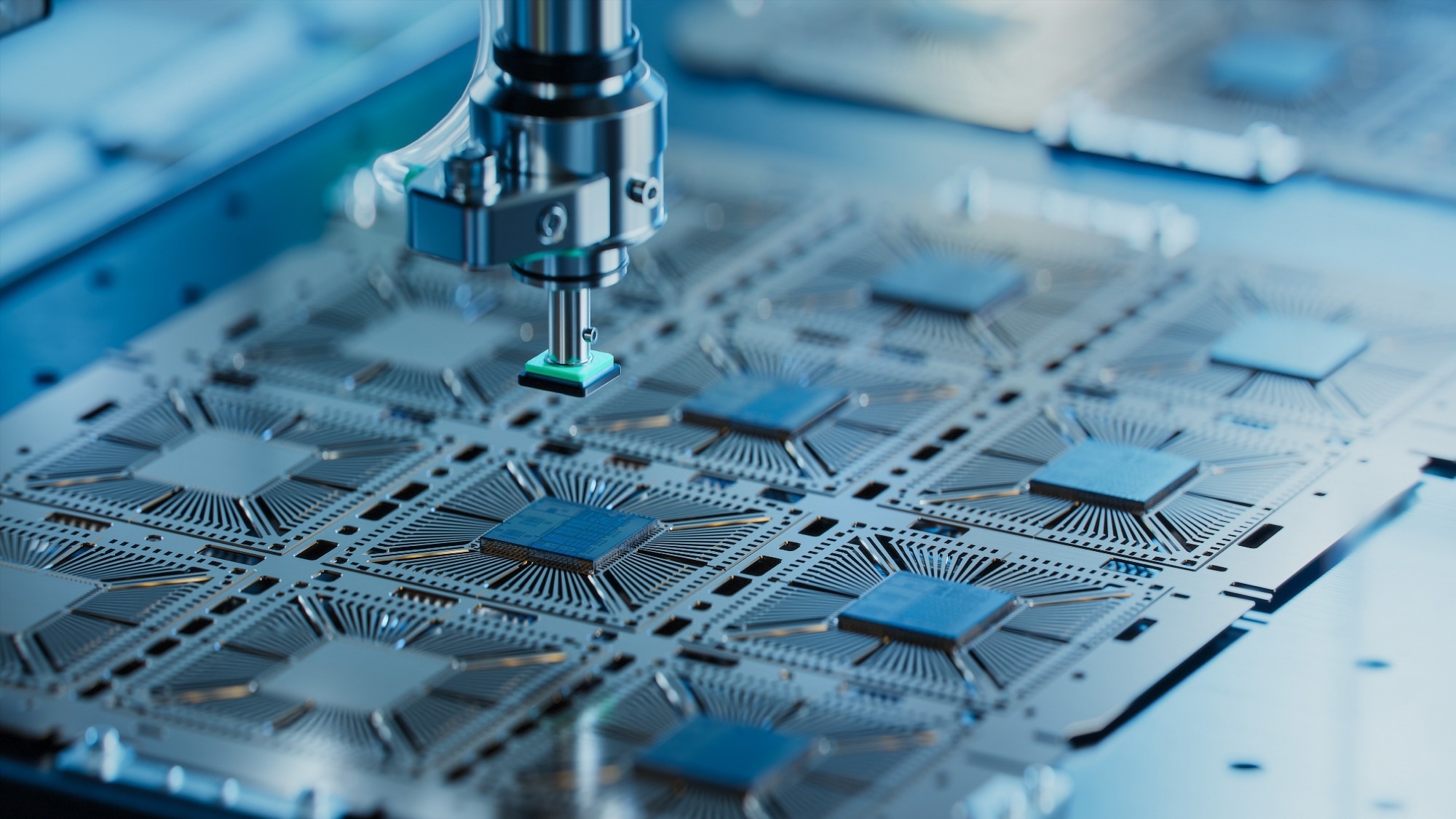

Study: Optofluidic three-dimensional microfabrication and nanofabrication. Image Credit: IM Imagery/Shutterstock.com

Study: Optofluidic three-dimensional microfabrication and nanofabrication. Image Credit: IM Imagery/Shutterstock.com

The team demonstrates the technique by building particle-based microfluidic valves capable of rapidly separating microparticles and nanoparticles by size, as well as multi-material microrobots that respond to magnetic, optical, and chemical stimuli.

Published recently in Nature, this approach could sidestep long-standing material limits in high-resolution 3D printing.

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

Three-dimensional micro- and nanofabrication techniques underpin advances in microrobotics, microactuators, and photonic devices.

Among them, two-photon polymerization (2PP) has become a leading method, valued for its sub-100-nanometre resolution and ability to print intricate free-form structures. However, 2PP is largely restricted to crosslinking polymers, limiting the range of functional materials that can be fabricated directly.

Researchers have tried to extend 2PP to non-polymeric materials by engineering specialised photoresists. For example, by chemically modifying inorganic nanoparticles or incorporating metal-coordination complexes.

These approaches, while effective in specific cases, remain narrowly tailored and lack broad material compatibility.

An alternative strategy is direct material assembly. Optical assembly methods use light-induced forces or fields to manipulate particles suspended in solution, but most existing techniques are confined to two-dimensional structures and typically operate at low throughput.

Using Light-Driven Flow to Assemble 3D Structures

The new method combines 2PP with optofluidic assembly. First, a hollow three-dimensional polymer template with a small opening, such as a cube, is fabricated on a glass substrate using 2PP.

The template is then immersed in a liquid containing uniformly dispersed nanoparticles or micrometre-scale particles.

A femtosecond laser, focused near the template opening, locally heats the fluid. This generates a sharp temperature gradient that drives a strong convective flow, reaching speeds of several millimetres per second.

Carried by this flow, particles are funneled into the hollow template, where they accumulate and assemble into a three-dimensional structure defined by the template geometry.

The researchers achieved an assembly rate of approximately 105 silica nanoparticles per minute. After assembly, the surrounding polymer template is removed using mild oxygen plasma treatment, leaving behind a free-standing, particle-based 3D microstructure.

Physics Behind the Assembly

The assembly process is governed by a balance between inter-particle forces and fluid-driven drag. Attractive interactions between particles - described by DLVO theory - must be strong enough to overcome hydrodynamic forces that tend to disperse them.

The researchers show that this balance can be tuned by adjusting solution conditions. Increasing ionic strength, for example by using sodium chloride concentrations of 0.5 M or higher, screens electrostatic repulsion between particles and promotes clustering.

Assembly also requires the optofluidic flow speed to remain below a critical threshold, where attractive forces can dominate over Stokes drag.

Laser heating plays a dual role. In addition to buoyancy-driven convection, localized solvent evaporation can generate transient bubbles. These bubbles introduce Marangoni flows driven by surface tension gradients, further accelerating particle transport into the template.

As a result, volumetric assembly speeds of around 700 µm3 per second were achieved, much faster than typical 2PP printing rates.

Broad Material Compatibility

Because the driving mechanism relies on light-induced fluid flow rather than material-specific optical forces, the technique is largely non-selective. The researchers assembled three-dimensional microstructures from a wide range of materials, including metals, metal oxides, diamond nanoparticles, nanowires, and quantum dots.

Despite the absence of chemical bonding or high-temperature sintering, the resulting structures remain mechanically stable. This stability arises from strong van der Waals interactions between densely packed nanoparticles, allowing the structures to be self-supporting immediately after template removal.

Multi-material architectures were created using sequential assembly steps, in which different particle suspensions were introduced one after another, with washing steps in between. This enabled precise spatial control over material composition within a single structure.

Microfluidic Valves and Microrobots

To demonstrate practical functionality, the team fabricated microfluidic chips containing particle-assembled microvalves embedded within polymer channels. These porous valves allow solvent to pass through rapidly while blocking nanoparticles above a size set by the valve’s internal pore structure.

By tuning valve dimensions and materials, the researchers achieved size-selective separation and enrichment of nanoparticles.

The approach was also used to build microrobots composed of multiple functional materials. By selectively integrating magnetic, catalytic, and photoactive nanoparticles, the researchers created microrobots capable of tumbling under magnetic fields, moving under ultraviolet light, or changing motion in chemical environments, sometimes within the same device.

A 3D Nano Printing Future

The optofluidic strategy could be a route to fabricating truly volumetric 3D micro- and nanostructures from materials that are difficult or impossible to print directly using conventional techniques.

While the current implementation relies on serial, laser-addressed assembly rather than parallel high-throughput manufacturing, it provides a powerful platform for integrating diverse materials with precise spatial control.

The researchers suggest that the method may support future advances in colloidal robotics, microphotonics, catalysis, and microfluidic systems: Areas where material diversity and three-dimensional architecture are essential.

Journal Reference

Lyu X., et al. (2026). Optofluidic three-dimensional microfabrication and nanofabrication. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10033-